Originally posted on Thursday, April 25th, 2013

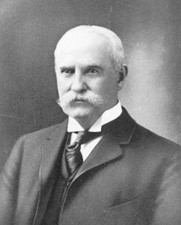

Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, an extremely influential political leader of his era, popularly called “General Manager of the Nation” (and ancestor of Vice President Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller), addressed the Economic Club of New York on November 29, 1909. His topic was the work of the National Monetary Commission which he had been instrumental in creating, chairing, and guiding and which laid the groundwork for the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Sen. Aldrich laid out, at length, the problem the National Monetary Commission sought to solve and the more stable European financial systems from which it sought to learn. An extract:

The crisis of 1907 was one of a series. I remember very well—although probably few of you do—the financial crash of 1873. I am sure you all remember that of 1893, from the effects of which the country did not recover for many years. Between 1900 and 1907 we had recurring periods of depression, of dangerous perturbations in the money market, when the Secretary of the Treasury was frantically called upon for assistance, and felt obliged to adopt the very questionable policy of making large deposits of public money in banks to relieve threatening situations.

If we should undertake to measure in dollars and cents the effects of these recurring periods of depression and of crisis, it would be an extremely difficult task. It is evident however, that while our country has natural advantages greater than those of any other, its normal growth and development have been greatly retarded by this periodical destruction of credit and confidence.

I believe that no one can carefully study the experience of the other great commercial nations without being convinced that disastrous results of recurring financial crises have been successfully prevented by a proper organization of capital and by the adoption of wise methods of banking and of currency.

Of course, until human nature is changed, it will not be possible to prevent, by legislation or otherwise, periods of overspeculation, with undue inflation of values and overextension of credit. When we consider the characteristics of the American people, whose unrivaled energy and enterprise are not always confined by the limits of prudence, it is certain that we in the United States shall always have periods of speculative inflation, with the evil results which are sure to follow. Other countries, however, have been able to prevent disastrous panics and to confine the evil results of overspeculation and inflation in the main to the people directly interested—that is, to the people who have violated the fundamental laws of business and to their financial backers and supporters.

There has been no general suspension of banking institutions and no general destruction of credit in any of the leading countries of Europe for more than half a century. There have been periods when great financial institutions or great merchants have failed and great losses have resulted, but at no time has there been any general suspension. It is now believed by competent authorities that the authorized suspension of the English bank act in 1847, I857, and 1866 could have been avoided by the use of the modern methods of treatment. These suspensions permitted the issue of an unlimited amount of notes by the Bank of England, but on only one of these occasions were any additional notes issued. In the other cases the mere announcement of the suspension restored confidence, and the business of the country went on.

Of no small contemporary interest: the Senator’s observations about the gold standard upon which his prescription of a central bank rested:

In this connection it is important to examine the methods adopted by the central banks to protect their reserves and to increase their holdings of gold when necessary. The means usually and successfully relied upon for these purposes is to advance the bank rate of discount high enough to attract gold from other countries. As in the case of commodities, gold follows the law of supply and demand; and if England bids more for gold than France or Germany she secures it. For example, in 1907 the Bank of England rapidly raised its rate of discount from 4 to 7 per cent. Mr. Campbell, the Governor of the Bank, told us the result was that gold came into the vaults of the Bank from 24 different countries, including British colonies. This enabled the Bank of England to protect its reserves and to furnish a large amount of gold for shipment to the United States. The power of the Bank of England to afford relief in all cases is extraordinary when we consider that the specie reserves of the Bank do not usually exceed $160,000,000. I asked the question, “What would have happened if the 7 per cent rate had not been effective?” The answer was, ” We should have advanced the rate up to 10 per cent if necessary and 10 per cent will bring gold out of the earth.”

The answer was intended, of course, merely as an indication of the power of a country that has credit and unlimited resources to bring gold to its coffers.

In recent years—certainly for nearly half a century—there has been no failure of this method to protect and increase the gold reserve of the great European banks.

Recent Comments